The panel included two survivors of the 1971 prison uprising and subsequent police massacre that shocked the nation.

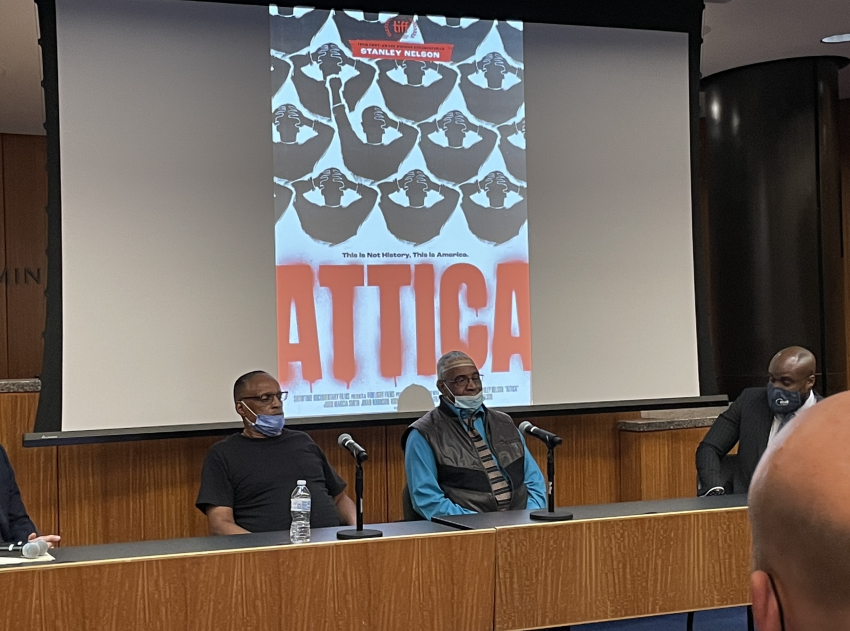

“There are many incomplete narratives about what happened… this film tells a story from the perspective of the survivors of the brutality,” Vincent Pullara, Legal Clinic Program Coordinator, said in his opening remarks. Cardozo’s Criminal Defense Clinic held the screening of the 2021 documentary film “Attica” on November 9 followed by a panel discussion with Tyrone Larkins and Lawrence Akil Killebrew, two men who were incarcerated at the Attica Correctional Facility during the 1971 Attica Prison Uprising.

The screening provided attendees with the unique opportunity to hear from survivors of the events of 1971 who are often left out of the narrative. Pullara said many accounts of the events at Attica have been incorrect, misrepresenting the inmates as murderous and misconstruing the event itself as a violent riot. The event was co-sponsored by the Public Service Scholars Program, Civil Rights Clinic and the E. Nathaniel Gates Scholars.

The film focuses on the survivors’ account of the 1971 prison uprising and subsequent massacre: a five-day standoff between mostly Black and Latino inmates protesting poor prison conditions and white law enforcement officers that ended when Governor Rockefeller of New York ordered a violent assault by law enforcement, leaving 43 incarcerated people and prison guards dead. On the 50th anniversary of the event, panelists said that little has changed in terms of the rights of incarcerated people in America. The Criminal Defense Clinic and its co-sponsors described the event as an educational opportunity for students who may not be familiar with the history at Attica.

“If tonight’s screening and conversation inspired just one person to be more involved in putting an end to these kinds of human atrocities, then this event will have been worth it,” said Bobby Codjoe, Director of Diversity and Inclusion, who introduced the film and panelists.

The film presents the background and context for the uprising, where inmates took control of the prison by forcing a locked door open, attacking a guard, and taking his master keys. The incarcerated men involved also took other prison guards as hostages to demand better living conditions at the prison including basic medical care, better visitation conditions and religious accommodations.

Following the screening, panelists Larkins and Killebrew spoke of their life experiences that they felt contributed to their incarceration and how they have since successfully reintegrated into society. Larkins is a counselor for youth involved in the Kings County Court in Brooklyn and Killebrew is a retired hotel chef who continues to volunteer in his free time.

“This is a wonderful film,” Killebrew said. “It shows what actually happened, without actors.” He also spoke of the lack of adequate personal hygiene supplies available to him while at Attica, the lack of religious freedom and the brutality of the guards. “Attica was the last stop,” he said. “If you wanted to be rehabilitated, you were in the wrong place.”

When asked by a student in the audience if he had advice for aspiring public defenders, Larkins stressed the importance of empathy and understanding. “Know that your client will be completely out of whack due to the degradation they experience in jail,” he said. “Consider criminal law because it’s where the real challenges are.”

The film was disturbing and often depicted graphic violence from the massacre. The conversation that followed with Killebrew and Larkins provided context and offered meaningful measures for reforms and hope for the future.